Common name: Ecuadorian or E

Latin Origins: compress

Distribution: West coast of America from Mexico (Lower California) to Chile. Only species definitely known from American West Coast, and restricted to this coast. Records from the Indo-West Pacific are mis-identifications

Habitat: Up to 1 km inland, mostly within 100 m of shore; sandy beaches, moist, heavily vegetated. [7]

Ecology: Mostly nocturnal, terrestrial

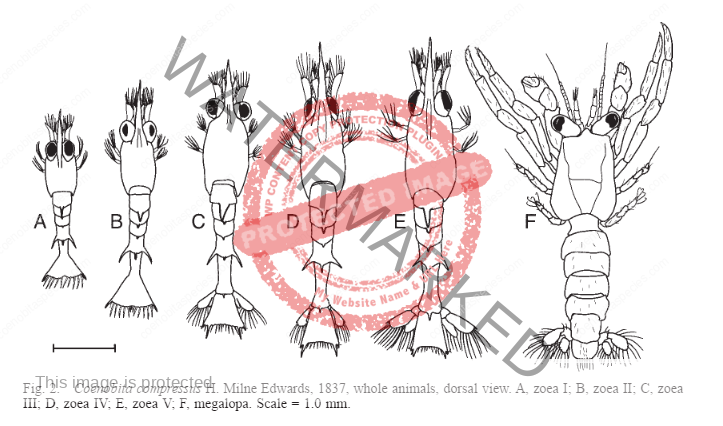

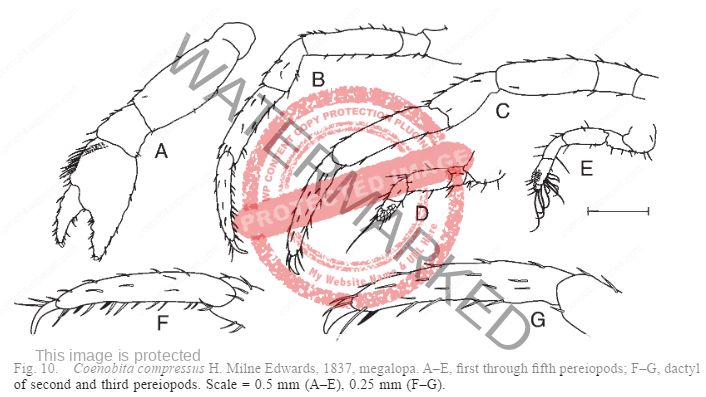

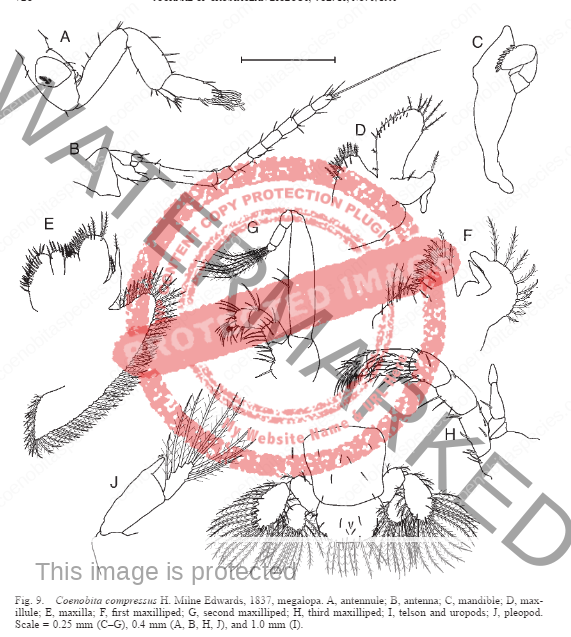

Lifecycle of larval stages: compressus passes through four or five laval stages, maximum time 31 days. Megalopa stage lasts 27-32 days. [4]

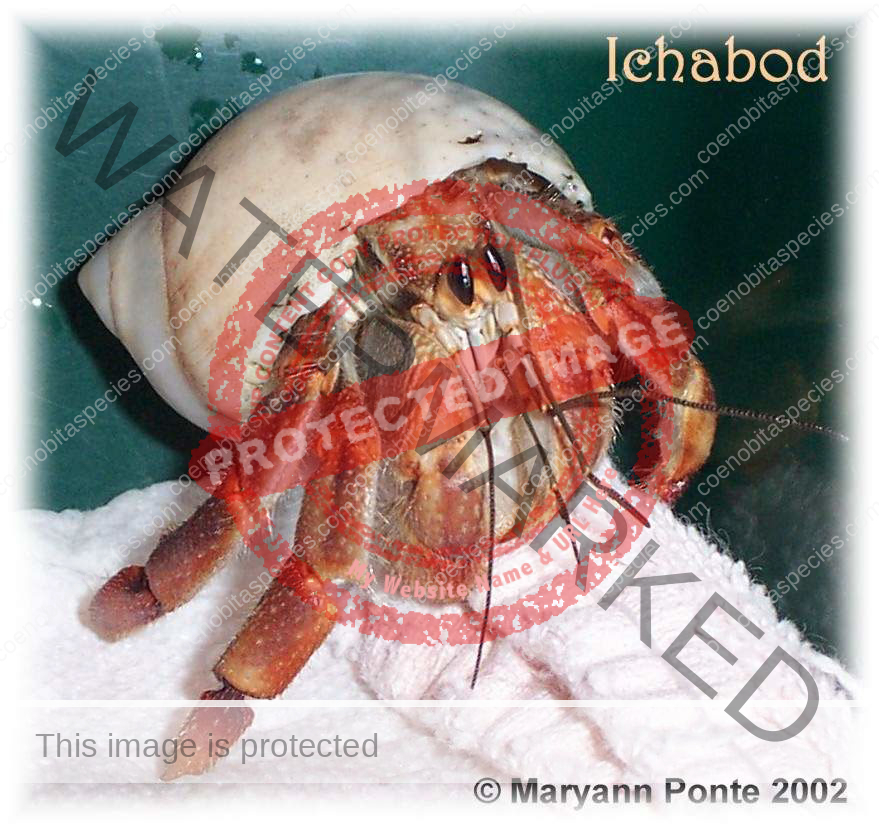

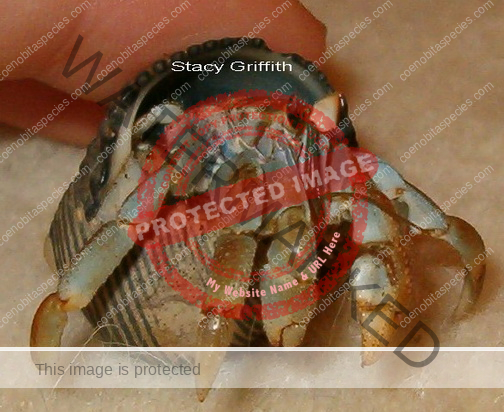

Characteristics: Juvenile compressus are often green or blue and the big pincer is tan. Legs often have dark stripes and the tips will begin to turn tan. As compressus grows its color becomes rich oranges and browns. The big pincer has noticeable stitch marks. They eyes are elongated. Unlike rugosus, there is no black marking on the eye stalk. The eyes are sometimes reddish in color like clypeatus. Behind the antenna on the carapace there is a black diagonal marking.

Behavior:

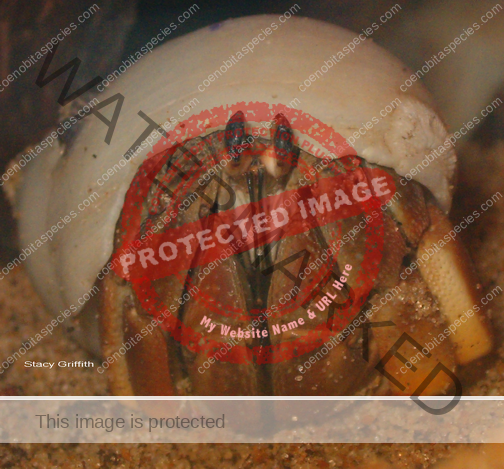

Compressus are notorious for being very picky about shells as they like a D shaped opening. This is the smallest of the species and does not grow much bigger than a ping pong ball. Compressus is fast no matter which direction they are running and is capable of chirping and seem to do so more readily than other species. Several hermit crab owners have noted this species has a specific molting difficulty which causes them to become trapped in their exo, unable to fully shed and therefore dying.

Ovigerous females often hide during the day, only becoming active at night. Small sized compressus are much more sensitive to desiccation than larger animals and great aggregations can be found under ledges and in caves where there is slightly more moisture.[2]

Males *may* grow considerably larger than the females. (This is based only on the observations of this one study) [2]

Natural History: Coenobita compressus are the most active at night, and in arid areas their activities are almost exclusively nocturnal. Activity usually begins in the evening shortly before sunset. About dawn the Coenobita begin seeking shelter and during the day great aggregations can be frequently be found under the leges, in small rocky caves, under logs and driftwood or dug into the sand. In humid vegetated areas many crabs remain active during the day; this being especially true of the smaller animals. At Bahia Tenancatita, Mexico many Coenobita were active in a moist shaded area near a lagoon during the day and then spread out onto the beach at night. [2]

Since shells, especially large ones, are scarce in many of the areas inhabited by Coenobita it seems likely that many of the shells now occupied by a hermit crabs have been passed around within the population over a period of many years. In this connection it is interesting to note that the majority of the shells occupied by Coenobita seem to be missing the columella. A similar observation has been made by Kinosita and Okajima on the shells of the Nerita striata occupied by Coenobita rugosus from Japan. These authors attribute the absence of the a columella to the chemical effects and mechanical abrasion by the abdominal appendages. [2]

A small bright green algae was noted coating the inside of the shells occupied by Coenobita at a number of localities. Magnus reported an apparently similar alga coating the inside of shells occupied by Coenobita jousseaumei on the Red Sea. [2]

Feeding on Feces – notably human [2]

Coenobita appear to do a great deal of apparently “aimless” exploring and I several times found them climbing in trees or bushes with no apparent goal. [2]

Agricultural pests; nocturnal in arid areas, active all day in humid areas [7]

Body mass 38g [7]

Diet: scavenger; cacao, platano, rice, wood fracments, ciruela, manzillo, fungus, palm copra, carrion [7]

Preferred shells: Nerites, Nassa Dorsatus, Thias

Common identifiers:

Eyes – elongated

Large claw – brown with stitch marks

Coloring – blue/green as juvenile, brown/orange as adult

Chirps – yes

C. compressus on Instagram

[insta-gallery id=”3″]

Photo Credits:

Jordan De Jong

Stacy Griffith

References:

1. Abrams, P., 1978. Shell selection and utilization in a terrestrial hermit crab,

Coenobita compressus (H. Milne Edwards). Oecologia 34: 239-253.

2. Ball, E. E., 1972. Observation on the biology of the hermit crab, Coenobita compressus H. Milne Edwards (Decapoda; Anomura) on the west coast of the Americas. Rev. Biol. Trop. 20(2): 265-273.

3. Brodie, R. J., 1999. Ontogeny of shell-related behaviors and transition to land in the terrestrial hermit crab Coenobita compressus H. Milne Edwards. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 241: 67-80.

4. Brodie, R. & A. W. Harvey, 2001. Larval development of the land hermit crab Coenobita compressus H. Milne Edwards reared in the laboratory. J. Crust. Biol. 21(3): 715-732.

5. Thacker, R. W., 1998. Avoidance of recently eaten foods by land hermit crabs, Coenobita compressus. Anim. Behav. 55(2): 485-496.

6. Thacker, R. W., 1996. Food choices of land hermit crabs (Coenobita compressus H. Milne Edwards) depend on past experience. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 199: 179‑191.

7. Biology of the Land Crabs 1st Edition by Warren W. Burggren, Brian R. McMahon

8. Land Cloabs of Costa Rica, Donald Bright

One comment

Comments are closed.